1. Introduction¶

Until recently, nearly every computer program that we interact with daily was coded by software developers from first principles. Say that we wanted to write an application to manage an e-commerce platform. After huddling around a whiteboard for a few hours to ponder the problem, we would come up with the broad strokes of a working solution that might probably look something like this: (i) users interact with the application through an interface running in a web browser or mobile application; (ii) our application interacts with a commercial-grade database engine to keep track of each user’s state and maintain records of historical transactions; and (iii) at the heart of our application, the business logic (you might say, the brains) of our application spells out in methodical detail the appropriate action that our program should take in every conceivable circumstance.

To build the brains of our application, we would have to step through every possible corner case that we anticipate encountering, devising appropriate rules. Each time a customer clicks to add an item to their shopping cart, we add an entry to the shopping cart database table, associating that user’s ID with the requested product’s ID. While few developers ever get it completely right the first time (it might take some test runs to work out the kinks), for the most part, we could write such a program from first principles and confidently launch it before ever seeing a real customer. Our ability to design automated systems from first principles that drive functioning products and systems, often in novel situations, is a remarkable cognitive feat. And when you are able to devise solutions that work \(100\%\) of the time, you should not be using machine learning.

Fortunately for the growing community of machine learning scientists, many tasks that we would like to automate do not bend so easily to human ingenuity. Imagine huddling around the whiteboard with the smartest minds you know, but this time you are tackling one of the following problems:

Write a program that predicts tomorrow’s weather given geographic information, satellite images, and a trailing window of past weather.

Write a program that takes in a question, expressed in free-form text, and answers it correctly.

Write a program that given an image can identify all the people it contains, drawing outlines around each.

Write a program that presents users with products that they are likely to enjoy but unlikely, in the natural course of browsing, to encounter.

In each of these cases, even elite programmers are incapable of coding up solutions from scratch. The reasons for this can vary. Sometimes the program that we are looking for follows a pattern that changes over time, and we need our programs to adapt. In other cases, the relationship (say between pixels, and abstract categories) may be too complicated, requiring thousands or millions of computations that are beyond our conscious understanding even if our eyes manage the task effortlessly. Machine learning is the study of powerful techniques that can learn from experience. As a machine learning algorithm accumulates more experience, typically in the form of observational data or interactions with an environment, its performance improves. Contrast this with our deterministic e-commerce platform, which performs according to the same business logic, no matter how much experience accrues, until the developers themselves learn and decide that it is time to update the software. In this book, we will teach you the fundamentals of machine learning, and focus in particular on deep learning, a powerful set of techniques driving innovations in areas as diverse as computer vision, natural language processing, healthcare, and genomics.

1.1. A Motivating Example¶

Before beginning writing, the authors of this book, like much of the work force, had to become caffeinated. We hopped in the car and started driving. Using an iPhone, Alex called out “Hey Siri”, awakening the phone’s voice recognition system. Then Mu commanded “directions to Blue Bottle coffee shop”. The phone quickly displayed the transcription of his command. It also recognized that we were asking for directions and launched the Maps application (app) to fulfill our request. Once launched, the Maps app identified a number of routes. Next to each route, the phone displayed a predicted transit time. While we fabricated this story for pedagogical convenience, it demonstrates that in the span of just a few seconds, our everyday interactions with a smart phone can engage several machine learning models.

Imagine just writing a program to respond to a wake word such as “Alexa”, “OK Google”, and “Hey Siri”. Try coding it up in a room by yourself with nothing but a computer and a code editor, as illustrated in Fig. 1.1.1. How would you write such a program from first principles? Think about it… the problem is hard. Every second, the microphone will collect roughly 44000 samples. Each sample is a measurement of the amplitude of the sound wave. What rule could map reliably from a snippet of raw audio to confident predictions \(\{\text{yes}, \text{no}\}\) on whether the snippet contains the wake word? If you are stuck, do not worry. We do not know how to write such a program from scratch either. That is why we use machine learning.

Fig. 1.1.1 Identify a wake word.¶

Here is the trick. Often, even when we do not know how to tell a computer explicitly how to map from inputs to outputs, we are nonetheless capable of performing the cognitive feat ourselves. In other words, even if you do not know how to program a computer to recognize the word “Alexa”, you yourself are able to recognize it. Armed with this ability, we can collect a huge dataset containing examples of audio and label those that do and that do not contain the wake word. In the machine learning approach, we do not attempt to design a system explicitly to recognize wake words. Instead, we define a flexible program whose behavior is determined by a number of parameters. Then we use the dataset to determine the best possible set of parameters, those that improve the performance of our program with respect to some measure of performance on the task of interest.

You can think of the parameters as knobs that we can turn, manipulating the behavior of the program. Fixing the parameters, we call the program a model. The set of all distinct programs (input-output mappings) that we can produce just by manipulating the parameters is called a family of models. And the meta-program that uses our dataset to choose the parameters is called a learning algorithm.

Before we can go ahead and engage the learning algorithm, we have to define the problem precisely, pinning down the exact nature of the inputs and outputs, and choosing an appropriate model family. In this case, our model receives a snippet of audio as input, and the model generates a selection among \(\{\text{yes}, \text{no}\}\) as output. If all goes according to plan the model’s guesses will typically be correct as to whether the snippet contains the wake word.

If we choose the right family of models, there should exist one setting of the knobs such that the model fires “yes” every time it hears the word “Alexa”. Because the exact choice of the wake word is arbitrary, we will probably need a model family sufficiently rich that, via another setting of the knobs, it could fire “yes” only upon hearing the word “Apricot”. We expect that the same model family should be suitable for “Alexa” recognition and “Apricot” recognition because they seem, intuitively, to be similar tasks. However, we might need a different family of models entirely if we want to deal with fundamentally different inputs or outputs, say if we wanted to map from images to captions, or from English sentences to Chinese sentences.

As you might guess, if we just set all of the knobs randomly, it is unlikely that our model will recognize “Alexa”, “Apricot”, or any other English word. In machine learning, the learning is the process by which we discover the right setting of the knobs coercing the desired behavior from our model. In other words, we train our model with data. As shown in Fig. 1.1.2, the training process usually looks like the following:

Start off with a randomly initialized model that cannot do anything useful.

Grab some of your data (e.g., audio snippets and corresponding \(\{\text{yes}, \text{no}\}\) labels).

Tweak the knobs so the model sucks less with respect to those examples.

Repeat Step 2 and 3 until the model is awesome.

Fig. 1.1.2 A typical training process.¶

To summarize, rather than code up a wake word recognizer, we code up a program that can learn to recognize wake words, if we present it with a large labeled dataset. You can think of this act of determining a program’s behavior by presenting it with a dataset as programming with data. That is to say, we can “program” a cat detector by providing our machine learning system with many examples of cats and dogs. This way the detector will eventually learn to emit a very large positive number if it is a cat, a very large negative number if it is a dog, and something closer to zero if it is not sure, and this barely scratches the surface of what machine learning can do. Deep learning, which we will explain in greater detail later, is just one among many popular methods for solving machine learning problems.

1.2. Key Components¶

In our wake word example, we described a dataset consisting of audio snippets and binary labels, and we gave a hand-wavy sense of how we might train a model to approximate a mapping from snippets to classifications. This sort of problem, where we try to predict a designated unknown label based on known inputs given a dataset consisting of examples for which the labels are known, is called supervised learning. This is just one among many kinds of machine learning problems. Later we will take a deep dive into different machine learning problems. First, we would like to shed more light on some core components that will follow us around, no matter what kind of machine learning problem we take on:

The data that we can learn from.

A model of how to transform the data.

An objective function that quantifies how well (or badly) the model is doing.

An algorithm to adjust the model’s parameters to optimize the objective function.

1.2.1. Data¶

It might go without saying that you cannot do data science without data. We could lose hundreds of pages pondering what precisely constitutes data, but for now, we will err on the practical side and focus on the key properties to be concerned with. Generally, we are concerned with a collection of examples. In order to work with data usefully, we typically need to come up with a suitable numerical representation. Each example (or data point, data instance, sample) typically consists of a set of attributes called features (or covariates), from which the model must make its predictions. In the supervised learning problems above, the thing to predict is a special attribute that is designated as the label (or target).

If we were working with image data, each individual photograph might constitute an example, each represented by an ordered list of numerical values corresponding to the brightness of each pixel. A \(200\times 200\) color photograph would consist of \(200\times200\times3=120000\) numerical values, corresponding to the brightness of the red, green, and blue channels for each spatial location. In another traditional task, we might try to predict whether or not a patient will survive, given a standard set of features such as age, vital signs, and diagnoses.

When every example is characterized by the same number of numerical values, we say that the data consist of fixed-length vectors and we describe the constant length of the vectors as the dimensionality of the data. As you might imagine, fixed-length can be a convenient property. If we wanted to train a model to recognize cancer in microscopy images, fixed-length inputs mean we have one less thing to worry about.

However, not all data can easily be represented as fixed-length vectors. While we might expect microscope images to come from standard equipment, we cannot expect images mined from the Internet to all show up with the same resolution or shape. For images, we might consider cropping them all to a standard size, but that strategy only gets us so far. We risk losing information in the cropped out portions. Moreover, text data resist fixed-length representations even more stubbornly. Consider the customer reviews left on e-commerce sites such as Amazon, IMDB, and TripAdvisor. Some are short: “it stinks!”. Others ramble for pages. One major advantage of deep learning over traditional methods is the comparative grace with which modern models can handle varying-length data.

Generally, the more data we have, the easier our job becomes. When we have more data, we can train more powerful models and rely less heavily on pre-conceived assumptions. The regime change from (comparatively) small to big data is a major contributor to the success of modern deep learning. To drive the point home, many of the most exciting models in deep learning do not work without large datasets. Some others work in the small data regime, but are no better than traditional approaches.

Finally, it is not enough to have lots of data and to process it cleverly. We need the right data. If the data are full of mistakes, or if the chosen features are not predictive of the target quantity of interest, learning is going to fail. The situation is captured well by the cliché: garbage in, garbage out. Moreover, poor predictive performance is not the only potential consequence. In sensitive applications of machine learning, like predictive policing, resume screening, and risk models used for lending, we must be especially alert to the consequences of garbage data. One common failure mode occurs in datasets where some groups of people are unrepresented in the training data. Imagine applying a skin cancer recognition system in the wild that had never seen black skin before. Failure can also occur when the data do not merely under-represent some groups but reflect societal prejudices. For example, if past hiring decisions are used to train a predictive model that will be used to screen resumes, then machine learning models could inadvertently capture and automate historical injustices. Note that this can all happen without the data scientist actively conspiring, or even being aware.

1.2.2. Models¶

Most machine learning involves transforming the data in some sense. We might want to build a system that ingests photos and predicts smiley-ness. Alternatively, we might want to ingest a set of sensor readings and predict how normal vs. anomalous the readings are. By model, we denote the computational machinery for ingesting data of one type, and spitting out predictions of a possibly different type. In particular, we are interested in statistical models that can be estimated from data. While simple models are perfectly capable of addressing appropriately simple problems, the problems that we focus on in this book stretch the limits of classical methods. Deep learning is differentiated from classical approaches principally by the set of powerful models that it focuses on. These models consist of many successive transformations of the data that are chained together top to bottom, thus the name deep learning. On our way to discussing deep models, we will also discuss some more traditional methods.

1.2.3. Objective Functions¶

Earlier, we introduced machine learning as learning from experience. By learning here, we mean improving at some task over time. But who is to say what constitutes an improvement? You might imagine that we could propose to update our model, and some people might disagree on whether the proposed update constituted an improvement or a decline.

In order to develop a formal mathematical system of learning machines, we need to have formal measures of how good (or bad) our models are. In machine learning, and optimization more generally, we call these objective functions. By convention, we usually define objective functions so that lower is better. This is merely a convention. You can take any function for which higher is better, and turn it into a new function that is qualitatively identical but for which lower is better by flipping the sign. Because lower is better, these functions are sometimes called loss functions.

When trying to predict numerical values, the most common loss function is squared error, i.e., the square of the difference between the prediction and the ground-truth. For classification, the most common objective is to minimize error rate, i.e., the fraction of examples on which our predictions disagree with the ground truth. Some objectives (e.g., squared error) are easy to optimize. Others (e.g., error rate) are difficult to optimize directly, owing to non-differentiability or other complications. In these cases, it is common to optimize a surrogate objective.

Typically, the loss function is defined with respect to the model’s parameters and depends upon the dataset. We learn the best values of our model’s parameters by minimizing the loss incurred on a set consisting of some number of examples collected for training. However, doing well on the training data does not guarantee that we will do well on unseen data. So we will typically want to split the available data into two partitions: the training dataset (or training set, for fitting model parameters) and the test dataset (or test set, which is held out for evaluation), reporting how the model performs on both of them. You could think of training performance as being like a student’s scores on practice exams used to prepare for some real final exam. Even if the results are encouraging, that does not guarantee success on the final exam. In other words, the test performance can deviate significantly from the training performance. When a model performs well on the training set but fails to generalize to unseen data, we say that it is overfitting. In real-life terms, this is like flunking the real exam despite doing well on practice exams.

1.2.4. Optimization Algorithms¶

Once we have got some data source and representation, a model, and a well-defined objective function, we need an algorithm capable of searching for the best possible parameters for minimizing the loss function. Popular optimization algorithms for deep learning are based on an approach called gradient descent. In short, at each step, this method checks to see, for each parameter, which way the training set loss would move if you perturbed that parameter just a small amount. It then updates the parameter in the direction that may reduce the loss.

1.3. Kinds of Machine Learning Problems¶

The wake word problem in our motivating example is just one among many problems that machine learning can tackle. To motivate the reader further and provide us with some common language when we talk about more problems throughout the book, in the following we list a sampling of machine learning problems. We will constantly refer to our aforementioned concepts such as data, models, and training techniques.

1.3.1. Supervised Learning¶

Supervised learning addresses the task of predicting labels given input features. Each feature–label pair is called an example. Sometimes, when the context is clear, we may use the term examples to refer to a collection of inputs, even when the corresponding labels are unknown. Our goal is to produce a model that maps any input to a label prediction.

To ground this description in a concrete example, if we were working in healthcare, then we might want to predict whether or not a patient would have a heart attack. This observation, “heart attack” or “no heart attack”, would be our label. The input features might be vital signs such as heart rate, diastolic blood pressure, and systolic blood pressure.

The supervision comes into play because for choosing the parameters, we (the supervisors) provide the model with a dataset consisting of labeled examples, where each example is matched with the ground-truth label. In probabilistic terms, we typically are interested in estimating the conditional probability of a label given input features. While it is just one among several paradigms within machine learning, supervised learning accounts for the majority of successful applications of machine learning in industry. Partly, that is because many important tasks can be described crisply as estimating the probability of something unknown given a particular set of available data:

Predict cancer vs. not cancer, given a computer tomography image.

Predict the correct translation in French, given a sentence in English.

Predict the price of a stock next month based on this month’s financial reporting data.

Even with the simple description “predicting labels given input features” supervised learning can take a great many forms and require a great many modeling decisions, depending on (among other considerations) the type, size, and the number of inputs and outputs. For example, we use different models to process sequences of arbitrary lengths and for processing fixed-length vector representations. We will visit many of these problems in depth throughout this book.

Informally, the learning process looks something like the following. First, grab a big collection of examples for which the features are known and select from them a random subset, acquiring the ground-truth labels for each. Sometimes these labels might be available data that have already been collected (e.g., did a patient die within the following year?) and other times we might need to employ human annotators to label the data, (e.g., assigning images to categories). Together, these inputs and corresponding labels comprise the training set. We feed the training dataset into a supervised learning algorithm, a function that takes as input a dataset and outputs another function: the learned model. Finally, we can feed previously unseen inputs to the learned model, using its outputs as predictions of the corresponding label. The full process is drawn in Fig. 1.3.1.

Fig. 1.3.1 Supervised learning.¶

1.3.1.1. Regression¶

Perhaps the simplest supervised learning task to wrap your head around is regression. Consider, for example, a set of data harvested from a database of home sales. We might construct a table, where each row corresponds to a different house, and each column corresponds to some relevant attribute, such as the square footage of a house, the number of bedrooms, the number of bathrooms, and the number of minutes (walking) to the center of town. In this dataset, each example would be a specific house, and the corresponding feature vector would be one row in the table. If you live in New York or San Francisco, and you are not the CEO of Amazon, Google, Microsoft, or Facebook, the (sq. footage, no. of bedrooms, no. of bathrooms, walking distance) feature vector for your home might look something like: \([600, 1, 1, 60]\). However, if you live in Pittsburgh, it might look more like \([3000, 4, 3, 10]\). Feature vectors like this are essential for most classic machine learning algorithms.

What makes a problem a regression is actually the output. Say that you are in the market for a new home. You might want to estimate the fair market value of a house, given some features like above. The label, the price of sale, is a numerical value. When labels take on arbitrary numerical values, we call this a regression problem. Our goal is to produce a model whose predictions closely approximate the actual label values.

Lots of practical problems are well-described regression problems. Predicting the rating that a user will assign to a movie can be thought of as a regression problem and if you designed a great algorithm to accomplish this feat in 2009, you might have won the 1-million-dollar Netflix prize. Predicting the length of stay for patients in the hospital is also a regression problem. A good rule of thumb is that any how much? or how many? problem should suggest regression, such as:

How many hours will this surgery take?

How much rainfall will this town have in the next six hours?

Even if you have never worked with machine learning before, you have probably worked through a regression problem informally. Imagine, for example, that you had your drains repaired and that your contractor spent 3 hours removing gunk from your sewage pipes. Then he sent you a bill of 350 dollars. Now imagine that your friend hired the same contractor for 2 hours and that he received a bill of 250 dollars. If someone then asked you how much to expect on their upcoming gunk-removal invoice you might make some reasonable assumptions, such as more hours worked costs more dollars. You might also assume that there is some base charge and that the contractor then charges per hour. If these assumptions held true, then given these two data examples, you could already identify the contractor’s pricing structure: 100 dollars per hour plus 50 dollars to show up at your house. If you followed that much then you already understand the high-level idea behind linear regression.

In this case, we could produce the parameters that exactly matched the contractor’s prices. Sometimes this is not possible, e.g., if some of the variance owes to a few factors besides your two features. In these cases, we will try to learn models that minimize the distance between our predictions and the observed values. In most of our chapters, we will focus on minimizing the squared error loss function. As we will see later, this loss corresponds to the assumption that our data were corrupted by Gaussian noise.

1.3.1.2. Classification¶

While regression models are great for addressing how many? questions, lots of problems do not bend comfortably to this template. For example, a bank wants to add check scanning to its mobile app. This would involve the customer snapping a photo of a check with their smart phone’s camera and the app would need to be able to automatically understand text seen in the image. Specifically, it would also need to understand handwritten text to be even more robust, such as mapping a handwritten character to one of the known characters. This kind of which one? problem is called classification. It is treated with a different set of algorithms than those used for regression although many techniques will carry over.

In classification, we want our model to look at features, e.g., the pixel values in an image, and then predict which category (formally called class), among some discrete set of options, an example belongs. For handwritten digits, we might have ten classes, corresponding to the digits 0 through 9. The simplest form of classification is when there are only two classes, a problem which we call binary classification. For example, our dataset could consist of images of animals and our labels might be the classes \(\mathrm{\{cat, dog\}}\). While in regression, we sought a regressor to output a numerical value, in classification, we seek a classifier, whose output is the predicted class assignment.

For reasons that we will get into as the book gets more technical, it can be hard to optimize a model that can only output a hard categorical assignment, e.g., either “cat” or “dog”. In these cases, it is usually much easier to instead express our model in the language of probabilities. Given features of an example, our model assigns a probability to each possible class. Returning to our animal classification example where the classes are \(\mathrm{\{cat, dog\}}\), a classifier might see an image and output the probability that the image is a cat as 0.9. We can interpret this number by saying that the classifier is 90% sure that the image depicts a cat. The magnitude of the probability for the predicted class conveys one notion of uncertainty. It is not the only notion of uncertainty and we will discuss others in more advanced chapters.

When we have more than two possible classes, we call the problem multiclass classification. Common examples include hand-written character recognition \(\mathrm{\{0, 1, 2, ... 9, a, b, c, ...\}}\). While we attacked regression problems by trying to minimize the squared error loss function, the common loss function for classification problems is called cross-entropy, whose name can be demystified via an introduction to information theory in subsequent chapters.

Note that the most likely class is not necessarily the one that you are going to use for your decision. Assume that you find a beautiful mushroom in your backyard as shown in Fig. 1.3.2.

Fig. 1.3.2 Death cap—do not eat!¶

Now, assume that you built a classifier and trained it to predict if a mushroom is poisonous based on a photograph. Say our poison-detection classifier outputs that the probability that Fig. 1.3.2 contains a death cap is 0.2. In other words, the classifier is 80% sure that our mushroom is not a death cap. Still, you would have to be a fool to eat it. That is because the certain benefit of a delicious dinner is not worth a 20% risk of dying from it. In other words, the effect of the uncertain risk outweighs the benefit by far. Thus, we need to compute the expected risk that we incur as the loss function, i.e., we need to multiply the probability of the outcome with the benefit (or harm) associated with it. In this case, the loss incurred by eating the mushroom can be \(0.2 \times \infty + 0.8 \times 0 = \infty\), whereas the loss of discarding it is \(0.2 \times 0 + 0.8 \times 1 = 0.8\). Our caution was justified: as any mycologist would tell us, the mushroom in Fig. 1.3.2 actually is a death cap.

Classification can get much more complicated than just binary, multiclass, or even multi-label classification. For instance, there are some variants of classification for addressing hierarchies. Hierarchies assume that there exist some relationships among the many classes. So not all errors are equal—if we must err, we would prefer to misclassify to a related class rather than to a distant class. Usually, this is referred to as hierarchical classification. One early example is due to Linnaeus, who organized the animals in a hierarchy.

In the case of animal classification, it might not be so bad to mistake a poodle (a dog breed) for a schnauzer (another dog breed), but our model would pay a huge penalty if it confused a poodle for a dinosaur. Which hierarchy is relevant might depend on how you plan to use the model. For example, rattle snakes and garter snakes might be close on the phylogenetic tree, but mistaking a rattler for a garter could be deadly.

1.3.1.3. Tagging¶

Some classification problems fit neatly into the binary or multiclass classification setups. For example, we could train a normal binary classifier to distinguish cats from dogs. Given the current state of computer vision, we can do this easily, with off-the-shelf tools. Nonetheless, no matter how accurate our model gets, we might find ourselves in trouble when the classifier encounters an image of the Town Musicians of Bremen, a popular German fairy tale featuring four animals in Fig. 1.3.3.

Fig. 1.3.3 A donkey, a dog, a cat, and a rooster.¶

As you can see, there is a cat in Fig. 1.3.3, and a rooster, a dog, and a donkey, with some trees in the background. Depending on what we want to do with our model ultimately, treating this as a binary classification problem might not make a lot of sense. Instead, we might want to give the model the option of saying the image depicts a cat, a dog, a donkey, and a rooster.

The problem of learning to predict classes that are not mutually exclusive is called multi-label classification. Auto-tagging problems are typically best described as multi-label classification problems. Think of the tags people might apply to posts on a technical blog, e.g., “machine learning”, “technology”, “gadgets”, “programming languages”, “Linux”, “cloud computing”, “AWS”. A typical article might have 5–10 tags applied because these concepts are correlated. Posts about “cloud computing” are likely to mention “AWS” and posts about “machine learning” could also deal with “programming languages”.

We also have to deal with this kind of problem when dealing with the biomedical literature, where correctly tagging articles is important because it allows researchers to do exhaustive reviews of the literature. At the National Library of Medicine, a number of professional annotators go over each article that gets indexed in PubMed to associate it with the relevant terms from MeSH, a collection of roughly 28000 tags. This is a time-consuming process and the annotators typically have a one-year lag between archiving and tagging. Machine learning can be used here to provide provisional tags until each article can have a proper manual review. Indeed, for several years, the BioASQ organization has hosted competitions to do precisely this.

1.3.1.4. Search¶

Sometimes we do not just want to assign each example to a bucket or to a real value. In the field of information retrieval, we want to impose a ranking on a set of items. Take web search for an example. The goal is less to determine whether a particular page is relevant for a query, but rather, which one of the plethora of search results is most relevant for a particular user. We really care about the ordering of the relevant search results and our learning algorithm needs to produce ordered subsets of elements from a larger set. In other words, if we are asked to produce the first 5 letters from the alphabet, there is a difference between returning “A B C D E” and “C A B E D”. Even if the result set is the same, the ordering within the set matters.

One possible solution to this problem is to first assign to every element in the set a corresponding relevance score and then to retrieve the top-rated elements. PageRank, the original secret sauce behind the Google search engine was an early example of such a scoring system but it was peculiar in that it did not depend on the actual query. Here they relied on a simple relevance filter to identify the set of relevant items and then on PageRank to order those results that contained the query term. Nowadays, search engines use machine learning and behavioral models to obtain query-dependent relevance scores. There are entire academic conferences devoted to this subject.

1.3.1.5. Recommender Systems¶

Recommender systems are another problem setting that is related to search and ranking. The problems are similar insofar as the goal is to display a set of relevant items to the user. The main difference is the emphasis on personalization to specific users in the context of recommender systems. For instance, for movie recommendations, the results page for a science fiction fan and the results page for a connoisseur of Peter Sellers comedies might differ significantly. Similar problems pop up in other recommendation settings, e.g., for retail products, music, and news recommendation.

In some cases, customers provide explicit feedback communicating how much they liked a particular product (e.g., the product ratings and reviews on Amazon, IMDb, and Goodreads). In some other cases, they provide implicit feedback, e.g., by skipping titles on a playlist, which might indicate dissatisfaction but might just indicate that the song was inappropriate in context. In the simplest formulations, these systems are trained to estimate some score, such as an estimated rating or the probability of purchase, given a user and an item.

Given such a model, for any given user, we could retrieve the set of objects with the largest scores, which could then be recommended to the user. Production systems are considerably more advanced and take detailed user activity and item characteristics into account when computing such scores. Fig. 1.3.4 is an example of deep learning books recommended by Amazon based on personalization algorithms tuned to capture one’s preferences.

Fig. 1.3.4 Deep learning books recommended by Amazon.¶

Despite their tremendous economic value, recommendation systems naively built on top of predictive models suffer some serious conceptual flaws. To start, we only observe censored feedback: users preferentially rate movies that they feel strongly about. For example, on a five-point scale, you might notice that items receive many five and one star ratings but that there are conspicuously few three-star ratings. Moreover, current purchase habits are often a result of the recommendation algorithm currently in place, but learning algorithms do not always take this detail into account. Thus it is possible for feedback loops to form where a recommender system preferentially pushes an item that is then taken to be better (due to greater purchases) and in turn is recommended even more frequently. Many of these problems about how to deal with censoring, incentives, and feedback loops, are important open research questions.

1.3.1.6. Sequence Learning¶

So far, we have looked at problems where we have some fixed number of inputs and produce a fixed number of outputs. For example, we considered predicting house prices from a fixed set of features: square footage, number of bedrooms, number of bathrooms, walking time to downtown. We also discussed mapping from an image (of fixed dimension) to the predicted probabilities that it belongs to each of a fixed number of classes, or taking a user ID and a product ID, and predicting a star rating. In these cases, once we feed our fixed-length input into the model to generate an output, the model immediately forgets what it just saw.

This might be fine if our inputs truly all have the same dimensions and if successive inputs truly have nothing to do with each other. But how would we deal with video snippets? In this case, each snippet might consist of a different number of frames. And our guess of what is going on in each frame might be much stronger if we take into account the previous or succeeding frames. Same goes for language. One popular deep learning problem is machine translation: the task of ingesting sentences in some source language and predicting their translation in another language.

These problems also occur in medicine. We might want a model to monitor patients in the intensive care unit and to fire off alerts if their risk of death in the next 24 hours exceeds some threshold. We definitely would not want this model to throw away everything it knows about the patient history each hour and just make its predictions based on the most recent measurements.

These problems are among the most exciting applications of machine learning and they are instances of sequence learning. They require a model to either ingest sequences of inputs or to emit sequences of outputs (or both). Specifically, sequence to sequence learning considers problems where input and output are both variable-length sequences, such as machine translation and transcribing text from the spoken speech. While it is impossible to consider all types of sequence transformations, the following special cases are worth mentioning.

Tagging and Parsing. This involves annotating a text sequence with attributes. In other words, the number of inputs and outputs is essentially the same. For instance, we might want to know where the verbs and subjects are. Alternatively, we might want to know which words are the named entities. In general, the goal is to decompose and annotate text based on structural and grammatical assumptions to get some annotation. This sounds more complex than it actually is. Below is a very simple example of annotating a sentence with tags indicating which words refer to named entities (tagged as “Ent”).

Tom has dinner in Washington with Sally

Ent - - - Ent - Ent

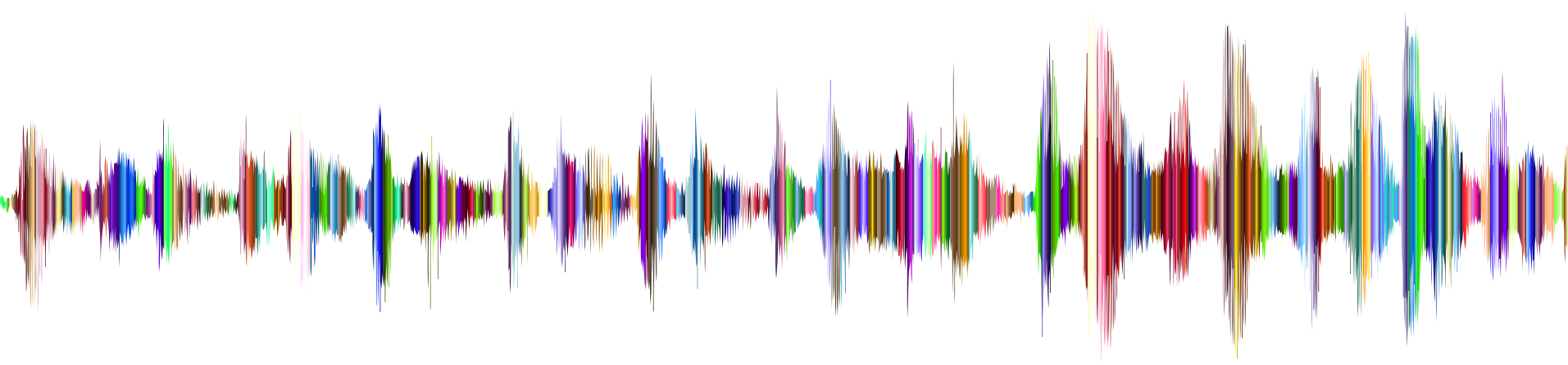

Automatic Speech Recognition. With speech recognition, the input sequence is an audio recording of a speaker (shown in Fig. 1.3.5), and the output is the textual transcript of what the speaker said. The challenge is that there are many more audio frames (sound is typically sampled at 8kHz or 16kHz) than text, i.e., there is no 1:1 correspondence between audio and text, since thousands of samples may correspond to a single spoken word. These are sequence to sequence learning problems where the output is much shorter than the input.

Fig. 1.3.5 -D-e-e-p- L-ea-r-ni-ng- in an audio recording.¶

Text to Speech. This is the inverse of automatic speech recognition. In other words, the input is text and the output is an audio file. In this case, the output is much longer than the input. While it is easy for humans to recognize a bad audio file, this is not quite so trivial for computers.

Machine Translation. Unlike the case of speech recognition, where corresponding inputs and outputs occur in the same order (after alignment), in machine translation, order inversion can be vital. In other words, while we are still converting one sequence into another, neither the number of inputs and outputs nor the order of corresponding data examples are assumed to be the same. Consider the following illustrative example of the peculiar tendency of Germans to place the verbs at the end of sentences.

German: Haben Sie sich schon dieses grossartige Lehrwerk angeschaut?

English: Did you already check out this excellent tutorial?

Wrong alignment: Did you yourself already this excellent tutorial looked-at?

Many related problems pop up in other learning tasks. For instance, determining the order in which a user reads a webpage is a two-dimensional layout analysis problem. Dialogue problems exhibit all kinds of additional complications, where determining what to say next requires taking into account real-world knowledge and the prior state of the conversation across long temporal distances. These are active areas of research.

1.3.2. Unsupervised and Self-Supervised Learning¶

All the examples so far were related to supervised learning, i.e., situations where we feed the model a giant dataset containing both the features and corresponding label values. You could think of the supervised learner as having an extremely specialized job and an extremely banal boss. The boss stands over your shoulder and tells you exactly what to do in every situation until you learn to map from situations to actions. Working for such a boss sounds pretty lame. On the other hand, it is easy to please this boss. You just recognize the pattern as quickly as possible and imitate their actions.

In a completely opposite way, it could be frustrating to work for a boss who has no idea what they want you to do. However, if you plan to be a data scientist, you had better get used to it. The boss might just hand you a giant dump of data and tell you to do some data science with it! This sounds vague because it is. We call this class of problems unsupervised learning, and the type and number of questions we could ask is limited only by our creativity. We will address unsupervised learning techniques in later chapters. To whet your appetite for now, we describe a few of the following questions you might ask.

Can we find a small number of prototypes that accurately summarize the data? Given a set of photos, can we group them into landscape photos, pictures of dogs, babies, cats, and mountain peaks? Likewise, given a collection of users’ browsing activities, can we group them into users with similar behavior? This problem is typically known as clustering.

Can we find a small number of parameters that accurately capture the relevant properties of the data? The trajectories of a ball are quite well described by velocity, diameter, and mass of the ball. Tailors have developed a small number of parameters that describe human body shape fairly accurately for the purpose of fitting clothes. These problems are referred to as subspace estimation. If the dependence is linear, it is called principal component analysis.

Is there a representation of (arbitrarily structured) objects in Euclidean space such that symbolic properties can be well matched? This can be used to describe entities and their relations, such as “Rome” \(-\) “Italy” \(+\) “France” \(=\) “Paris”.

Is there a description of the root causes of much of the data that we observe? For instance, if we have demographic data about house prices, pollution, crime, location, education, and salaries, can we discover how they are related simply based on empirical data? The fields concerned with causality and probabilistic graphical models address this problem.

Another important and exciting recent development in unsupervised learning is the advent of generative adversarial networks. These give us a procedural way to synthesize data, even complicated structured data like images and audio. The underlying statistical mechanisms are tests to check whether real and fake data are the same.

As a form of unsupervised learning, self-supervised learning leverages unlabeled data to provide supervision in training, such as by predicting some withheld part of the data using other parts. For text, we can train models to “fill in the blanks” by predicting randomly masked words using their surrounding words (contexts) in big corpora without any labeling effort ()! For images, we may train models to tell the relative position between two cropped regions of the same image (). In these two examples of self-supervised learning, training models to predict possible words and relative positions are both classification tasks (from supervised learning).

1.3.3. Interacting with an Environment¶

So far, we have not discussed where data actually come from, or what actually happens when a machine learning model generates an output. That is because supervised learning and unsupervised learning do not address these issues in a very sophisticated way. In either case, we grab a big pile of data upfront, then set our pattern recognition machines in motion without ever interacting with the environment again. Because all of the learning takes place after the algorithm is disconnected from the environment, this is sometimes called offline learning. For supervised learning, the process by considering data collection from an environment looks like Fig. 1.3.6.

Fig. 1.3.6 Collecting data for supervised learning from an environment.¶

This simplicity of offline learning has its charms. The upside is that we can worry about pattern recognition in isolation, without any distraction from these other problems. But the downside is that the problem formulation is quite limiting. If you are more ambitious, or if you grew up reading Asimov’s Robot series, then you might imagine artificially intelligent bots capable not only of making predictions, but also of taking actions in the world. We want to think about intelligent agents, not just predictive models. This means that we need to think about choosing actions, not just making predictions. Moreover, unlike predictions, actions actually impact the environment. If we want to train an intelligent agent, we must account for the way its actions might impact the future observations of the agent.

Considering the interaction with an environment opens a whole set of new modeling questions. The following are just a few examples.

Does the environment remember what we did previously?

Does the environment want to help us, e.g., a user reading text into a speech recognizer?

Does the environment want to beat us, i.e., an adversarial setting like spam filtering (against spammers) or playing a game (vs. an opponent)?

Does the environment not care?

Does the environment have shifting dynamics? For example, does future data always resemble the past or do the patterns change over time, either naturally or in response to our automated tools?

This last question raises the problem of distribution shift, when training and test data are different. It is a problem that most of us have experienced when taking exams written by a lecturer, while the homework was composed by his teaching assistants. Next, we will briefly describe reinforcement learning, a setting that explicitly considers interactions with an environment.

1.3.4. Reinforcement Learning¶

If you are interested in using machine learning to develop an agent that interacts with an environment and takes actions, then you are probably going to wind up focusing on reinforcement learning. This might include applications to robotics, to dialogue systems, and even to developing artificial intelligence (AI) for video games. Deep reinforcement learning, which applies deep learning to reinforcement learning problems, has surged in popularity. The breakthrough deep Q-network that beat humans at Atari games using only the visual input, and the AlphaGo program that dethroned the world champion at the board game Go are two prominent examples.

Reinforcement learning gives a very general statement of a problem, in which an agent interacts with an environment over a series of time steps. At each time step, the agent receives some observation from the environment and must choose an action that is subsequently transmitted back to the environment via some mechanism (sometimes called an actuator). Finally, the agent receives a reward from the environment. This process is illustrated in Fig. 1.3.7. The agent then receives a subsequent observation, and chooses a subsequent action, and so on. The behavior of a reinforcement learning agent is governed by a policy. In short, a policy is just a function that maps from observations of the environment to actions. The goal of reinforcement learning is to produce a good policy.

Fig. 1.3.7 The interaction between reinforcement learning and an environment.¶

It is hard to overstate the generality of the reinforcement learning framework. For example, we can cast any supervised learning problem as a reinforcement learning problem. Say we had a classification problem. We could create a reinforcement learning agent with one action corresponding to each class. We could then create an environment which gave a reward that was exactly equal to the loss function from the original supervised learning problem.

That being said, reinforcement learning can also address many problems that supervised learning cannot. For example, in supervised learning we always expect that the training input comes associated with the correct label. But in reinforcement learning, we do not assume that for each observation the environment tells us the optimal action. In general, we just get some reward. Moreover, the environment may not even tell us which actions led to the reward.

Consider for example the game of chess. The only real reward signal comes at the end of the game when we either win, which we might assign a reward of 1, or when we lose, which we could assign a reward of -1. So reinforcement learners must deal with the credit assignment problem: determining which actions to credit or blame for an outcome. The same goes for an employee who gets a promotion on October 11. That promotion likely reflects a large number of well-chosen actions over the previous year. Getting more promotions in the future requires figuring out what actions along the way led to the promotion.

Reinforcement learners may also have to deal with the problem of partial observability. That is, the current observation might not tell you everything about your current state. Say a cleaning robot found itself trapped in one of many identical closets in a house. Inferring the precise location (and thus state) of the robot might require considering its previous observations before entering the closet.

Finally, at any given point, reinforcement learners might know of one good policy, but there might be many other better policies that the agent has never tried. The reinforcement learner must constantly choose whether to exploit the best currently-known strategy as a policy, or to explore the space of strategies, potentially giving up some short-run reward in exchange for knowledge.

The general reinforcement learning problem is a very general setting. Actions affect subsequent observations. Rewards are only observed corresponding to the chosen actions. The environment may be either fully or partially observed. Accounting for all this complexity at once may ask too much of researchers. Moreover, not every practical problem exhibits all this complexity. As a result, researchers have studied a number of special cases of reinforcement learning problems.

When the environment is fully observed, we call the reinforcement learning problem a Markov decision process. When the state does not depend on the previous actions, we call the problem a contextual bandit problem. When there is no state, just a set of available actions with initially unknown rewards, this problem is the classic multi-armed bandit problem.

1.4. Roots¶

We have just reviewed a small subset of problems that machine learning can address. For a diverse set of machine learning problems, deep learning provides powerful tools for solving them. Although many deep learning methods are recent inventions, the core idea of programming with data and neural networks (names of many deep learning models) has been studied for centuries. In fact, humans have held the desire to analyze data and to predict future outcomes for long and much of natural science has its roots in this. For instance, the Bernoulli distribution is named after Jacob Bernoulli (1655–1705), and the Gaussian distribution was discovered by Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855). He invented, for instance, the least mean squares algorithm, which is still used today for countless problems from insurance calculations to medical diagnostics. These tools gave rise to an experimental approach in the natural sciences—for instance, Ohm’s law relating current and voltage in a resistor is perfectly described by a linear model.

Even in the middle ages, mathematicians had a keen intuition of estimates. For instance, the geometry book of Jacob Köbel (1460–1533) illustrates averaging the length of 16 adult men’s feet to obtain the average foot length.

Fig. 1.4.1 Estimating the length of a foot.¶

Fig. 1.4.1 illustrates how this estimator works. The 16 adult men were asked to line up in a row, when leaving the church. Their aggregate length was then divided by 16 to obtain an estimate for what now amounts to 1 foot. This “algorithm” was later improved to deal with misshapen feet—the 2 men with the shortest and longest feet respectively were sent away, averaging only over the remainder. This is one of the earliest examples of the trimmed mean estimate.

Statistics really took off with the collection and availability of data. One of its titans, Ronald Fisher (1890–1962), contributed significantly to its theory and also its applications in genetics. Many of his algorithms (such as linear discriminant analysis) and formula (such as the Fisher information matrix) are still in frequent use today. In fact, even the Iris dataset that Fisher released in 1936 is still used sometimes to illustrate machine learning algorithms. He was also a proponent of eugenics, which should remind us that the morally dubious use of data science has as long and enduring a history as its productive use in industry and the natural sciences.

A second influence for machine learning came from information theory by Claude Shannon (1916–2001) and the theory of computation via Alan Turing (1912–1954). Turing posed the question “can machines think?” in his famous paper Computing Machinery and Intelligence (). In what he described as the Turing test, a machine can be considered intelligent if it is difficult for a human evaluator to distinguish between the replies from a machine and a human based on textual interactions.

Another influence can be found in neuroscience and psychology. After all, humans clearly exhibit intelligent behavior. It is thus only reasonable to ask whether one could explain and possibly reverse engineer this capacity. One of the oldest algorithms inspired in this fashion was formulated by Donald Hebb (1904–1985). In his groundbreaking book The Organization of Behavior (), he posited that neurons learn by positive reinforcement. This became known as the Hebbian learning rule. It is the prototype of Rosenblatt’s perceptron learning algorithm and it laid the foundations of many stochastic gradient descent algorithms that underpin deep learning today: reinforce desirable behavior and diminish undesirable behavior to obtain good settings of the parameters in a neural network.

Biological inspiration is what gave neural networks their name. For over a century (dating back to the models of Alexander Bain, 1873 and James Sherrington, 1890), researchers have tried to assemble computational circuits that resemble networks of interacting neurons. Over time, the interpretation of biology has become less literal but the name stuck. At its heart, lie a few key principles that can be found in most networks today:

The alternation of linear and nonlinear processing units, often referred to as layers.

The use of the chain rule (also known as backpropagation) for adjusting parameters in the entire network at once.

After initial rapid progress, research in neural networks languished from around 1995 until 2005. This was mainly due to two reasons. First, training a network is computationally very expensive. While random-access memory was plentiful at the end of the past century, computational power was scarce. Second, datasets were relatively small. In fact, Fisher’s Iris dataset from 1932 was a popular tool for testing the efficacy of algorithms. The MNIST dataset with its 60000 handwritten digits was considered huge.

Given the scarcity of data and computation, strong statistical tools such as kernel methods, decision trees and graphical models proved empirically superior. Unlike neural networks, they did not require weeks to train and provided predictable results with strong theoretical guarantees.

1.5. The Road to Deep Learning¶

Much of this changed with the ready availability of large amounts of data, due to the World Wide Web, the advent of companies serving hundreds of millions of users online, a dissemination of cheap, high-quality sensors, cheap data storage (Kryder’s law), and cheap computation (Moore’s law), in particular in the form of GPUs, originally engineered for computer gaming. Suddenly algorithms and models that seemed computationally infeasible became relevant (and vice versa). This is best illustrated in Section 1.5.

Decade |

Dataset |

Memory |

Floating point calculations per second |

|---|---|---|---|

1970 |

100 (Iris) |

1 KB |

100 KF (Intel 8080) |

1980 |

1 K (House prices in Boston) |

100 KB |

1 MF (Intel 80186) |

1990 |

10 K (optical character recognition) |

10 MB |

10 MF (Intel 80486) |

2000 |

10 M (web pages) |

100 MB |

1 GF (Intel Core) |

2010 |

10 G (advertising) |

1 GB |

1 TF (Nvidia C2050) |

2020 |

1 T (social network) |

100 GB |

1 PF (Nvidia DGX-2) |

Table: Dataset vs. computer memory and computational power

It is evident that random-access memory has not kept pace with the growth in data. At the same time, the increase in computational power has outpaced that of the data available. This means that statistical models need to become more memory efficient (this is typically achieved by adding nonlinearities) while simultaneously being able to spend more time on optimizing these parameters, due to an increased computational budget. Consequently, the sweet spot in machine learning and statistics moved from (generalized) linear models and kernel methods to deep neural networks. This is also one of the reasons why many of the mainstays of deep learning, such as multilayer perceptrons (), convolutional neural networks (), long short-term memory (), and Q-Learning (), were essentially “rediscovered” in the past decade, after laying comparatively dormant for considerable time.

The recent progress in statistical models, applications, and algorithms has sometimes been likened to the Cambrian explosion: a moment of rapid progress in the evolution of species. Indeed, the state of the art is not just a mere consequence of available resources, applied to decades old algorithms. Note that the list below barely scratches the surface of the ideas that have helped researchers achieve tremendous progress over the past decade.

Novel methods for capacity control, such as dropout (), have helped to mitigate the danger of overfitting. This was achieved by applying noise injection () throughout the neural network, replacing weights by random variables for training purposes.

Attention mechanisms solved a second problem that had plagued statistics for over a century: how to increase the memory and complexity of a system without increasing the number of learnable parameters. Researchers found an elegant solution by using what can only be viewed as a learnable pointer structure (). Rather than having to remember an entire text sequence, e.g., for machine translation in a fixed-dimensional representation, all that needed to be stored was a pointer to the intermediate state of the translation process. This allowed for significantly increased accuracy for long sequences, since the model no longer needed to remember the entire sequence before commencing the generation of a new sequence.

Multi-stage designs, e.g., via the memory networks () and the neural programmer-interpreter () allowed statistical modelers to describe iterative approaches to reasoning. These tools allow for an internal state of the deep neural network to be modified repeatedly, thus carrying out subsequent steps in a chain of reasoning, similar to how a processor can modify memory for a computation.

Another key development was the invention of generative adversarial networks (). Traditionally, statistical methods for density estimation and generative models focused on finding proper probability distributions and (often approximate) algorithms for sampling from them. As a result, these algorithms were largely limited by the lack of flexibility inherent in the statistical models. The crucial innovation in generative adversarial networks was to replace the sampler by an arbitrary algorithm with differentiable parameters. These are then adjusted in such a way that the discriminator (effectively a two-sample test) cannot distinguish fake from real data. Through the ability to use arbitrary algorithms to generate data, it opened up density estimation to a wide variety of techniques. Examples of galloping Zebras () and of fake celebrity faces () are both testimony to this progress. Even amateur doodlers can produce photorealistic images based on just sketches that describe how the layout of a scene looks like ().

In many cases, a single GPU is insufficient to process the large amounts of data available for training. Over the past decade the ability to build parallel and distributed training algorithms has improved significantly. One of the key challenges in designing scalable algorithms is that the workhorse of deep learning optimization, stochastic gradient descent, relies on relatively small minibatches of data to be processed. At the same time, small batches limit the efficiency of GPUs. Hence, training on 1024 GPUs with a minibatch size of, say 32 images per batch amounts to an aggregate minibatch of about 32000 images. Recent work, first by Li (), and subsequently by () and () pushed the size up to 64000 observations, reducing training time for the ResNet-50 model on the ImageNet dataset to less than 7 minutes. For comparison—initially training times were measured in the order of days.

The ability to parallelize computation has also contributed quite crucially to progress in reinforcement learning, at least whenever simulation is an option. This has led to significant progress in computers achieving superhuman performance in Go, Atari games, Starcraft, and in physics simulations (e.g., using MuJoCo). See e.g., () for a description of how to achieve this in AlphaGo. In a nutshell, reinforcement learning works best if plenty of (state, action, reward) triples are available, i.e., whenever it is possible to try out lots of things to learn how they relate to each other. Simulation provides such an avenue.

Deep learning frameworks have played a crucial role in disseminating ideas. The first generation of frameworks allowing for easy modeling encompassed Caffe, Torch, and Theano. Many seminal papers were written using these tools. By now, they have been superseded by TensorFlow (often used via its high level API Keras), CNTK, Caffe 2, and Apache MXNet. The third generation of tools, namely imperative tools for deep learning, was arguably spearheaded by Chainer, which used a syntax similar to Python NumPy to describe models. This idea was adopted by both PyTorch, the Gluon API of MXNet, and Jax.

The division of labor between system researchers building better tools and statistical modelers building better neural networks has greatly simplified things. For instance, training a linear logistic regression model used to be a nontrivial homework problem, worthy to give to new machine learning Ph.D. students at Carnegie Mellon University in 2014. By now, this task can be accomplished with less than 10 lines of code, putting it firmly into the grasp of programmers.

1.6. Success Stories¶

AI has a long history of delivering results that would be difficult to accomplish otherwise. For instance, the mail sorting systems using optical character recognition have been deployed since the 1990s. This is, after all, the source of the famous MNIST dataset of handwritten digits. The same applies to reading checks for bank deposits and scoring creditworthiness of applicants. Financial transactions are checked for fraud automatically. This forms the backbone of many e-commerce payment systems, such as PayPal, Stripe, AliPay, WeChat, Apple, Visa, and MasterCard. Computer programs for chess have been competitive for decades. Machine learning feeds search, recommendation, personalization, and ranking on the Internet. In other words, machine learning is pervasive, albeit often hidden from sight.

It is only recently that AI has been in the limelight, mostly due to solutions to problems that were considered intractable previously and that are directly related to consumers. Many of such advances are attributed to deep learning.

Intelligent assistants, such as Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, and Google’s assistant, are able to answer spoken questions with a reasonable degree of accuracy. This includes menial tasks such as turning on light switches (a boon to the disabled) up to making barber’s appointments and offering phone support dialog. This is likely the most noticeable sign that AI is affecting our lives.

A key ingredient in digital assistants is the ability to recognize speech accurately. Gradually the accuracy of such systems has increased to the point where they reach human parity for certain applications ().

Object recognition likewise has come a long way. Estimating the object in a picture was a fairly challenging task in 2010. On the ImageNet benchmark researchers from NEC Labs and University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign achieved a top-5 error rate of 28% (). By 2017, this error rate was reduced to 2.25% (). Similarly, stunning results have been achieved for identifying birds or diagnosing skin cancer.

Games used to be a bastion of human intelligence. Starting from TD-Gammon, a program for playing backgammon using temporal difference reinforcement learning, algorithmic and computational progress has led to algorithms for a wide range of applications. Unlike backgammon, chess has a much more complex state space and set of actions. DeepBlue beat Garry Kasparov using massive parallelism, special-purpose hardware and efficient search through the game tree (). Go is more difficult still, due to its huge state space. AlphaGo reached human parity in 2015, using deep learning combined with Monte Carlo tree sampling (). The challenge in Poker was that the state space is large and it is not fully observed (we do not know the opponents’ cards). Libratus exceeded human performance in Poker using efficiently structured strategies (). This illustrates the impressive progress in games and the fact that advanced algorithms played a crucial part in them.

Another indication of progress in AI is the advent of self-driving cars and trucks. While full autonomy is not quite within reach yet, excellent progress has been made in this direction, with companies such as Tesla, NVIDIA, and Waymo shipping products that enable at least partial autonomy. What makes full autonomy so challenging is that proper driving requires the ability to perceive, to reason and to incorporate rules into a system. At present, deep learning is used primarily in the computer vision aspect of these problems. The rest is heavily tuned by engineers.

Again, the above list barely scratches the surface of where machine learning has impacted practical applications. For instance, robotics, logistics, computational biology, particle physics, and astronomy owe some of their most impressive recent advances at least in parts to machine learning. Machine learning is thus becoming a ubiquitous tool for engineers and scientists.

Frequently, the question of the AI apocalypse, or the AI singularity has been raised in non-technical articles on AI. The fear is that somehow machine learning systems will become sentient and decide independently from their programmers (and masters) about things that directly affect the livelihood of humans. To some extent, AI already affects the livelihood of humans in an immediate way: creditworthiness is assessed automatically, autopilots mostly navigate vehicles, decisions about whether to grant bail use statistical data as input. More frivolously, we can ask Alexa to switch on the coffee machine.

Fortunately, we are far from a sentient AI system that is ready to manipulate its human creators (or burn their coffee). First, AI systems are engineered, trained and deployed in a specific, goal-oriented manner. While their behavior might give the illusion of general intelligence, it is a combination of rules, heuristics and statistical models that underlie the design. Second, at present tools for artificial general intelligence simply do not exist that are able to improve themselves, reason about themselves, and that are able to modify, extend, and improve their own architecture while trying to solve general tasks.

A much more pressing concern is how AI is being used in our daily lives. It is likely that many menial tasks fulfilled by truck drivers and shop assistants can and will be automated. Farm robots will likely reduce the cost for organic farming but they will also automate harvesting operations. This phase of the industrial revolution may have profound consequences on large swaths of society, since truck drivers and shop assistants are some of the most common jobs in many countries. Furthermore, statistical models, when applied without care can lead to racial, gender, or age bias and raise reasonable concerns about procedural fairness if automated to drive consequential decisions. It is important to ensure that these algorithms are used with care. With what we know today, this strikes us a much more pressing concern than the potential of malevolent superintelligence to destroy humanity.

1.7. Characteristics¶

Thus far, we have talked about machine learning broadly, which is both a branch of AI and an approach to AI. Though deep learning is a subset of machine learning, the dizzying set of algorithms and applications makes it difficult to assess what specifically the ingredients for deep learning might be. This is as difficult as trying to pin down required ingredients for pizza since almost every component is substitutable.

As we have described, machine learning can use data to learn transformations between inputs and outputs, such as transforming audio into text in speech recognition. In doing so, it is often necessary to represent data in a way suitable for algorithms to transform such representations into the output. Deep learning is deep in precisely the sense that its models learn many layers of transformations, where each layer offers the representation at one level. For example, layers near the input may represent low-level details of the data, while layers closer to the classification output may represent more abstract concepts used for discrimination. Since representation learning aims at finding the representation itself, deep learning can be referred to as multi-level representation learning.

The problems that we have discussed so far, such as learning from the raw audio signal, the raw pixel values of images, or mapping between sentences of arbitrary lengths and their counterparts in foreign languages, are those where deep learning excels and where traditional machine learning methods falter. It turns out that these many-layered models are capable of addressing low-level perceptual data in a way that previous tools could not. Arguably the most significant commonality in deep learning methods is the use of end-to-end training. That is, rather than assembling a system based on components that are individually tuned, one builds the system and then tunes their performance jointly. For instance, in computer vision scientists used to separate the process of feature engineering from the process of building machine learning models. The Canny edge detector () and Lowe’s SIFT feature extractor () reigned supreme for over a decade as algorithms for mapping images into feature vectors. In bygone days, the crucial part of applying machine learning to these problems consisted of coming up with manually-engineered ways of transforming the data into some form amenable to shallow models. Unfortunately, there is only so little that humans can accomplish by ingenuity in comparison with a consistent evaluation over millions of choices carried out automatically by an algorithm. When deep learning took over, these feature extractors were replaced by automatically tuned filters, yielding superior accuracy.

Thus, one key advantage of deep learning is that it replaces not only the shallow models at the end of traditional learning pipelines, but also the labor-intensive process of feature engineering. Moreover, by replacing much of the domain-specific preprocessing, deep learning has eliminated many of the boundaries that previously separated computer vision, speech recognition, natural language processing, medical informatics, and other application areas, offering a unified set of tools for tackling diverse problems.

Beyond end-to-end training, we are experiencing a transition from parametric statistical descriptions to fully nonparametric models. When data are scarce, one needs to rely on simplifying assumptions about reality in order to obtain useful models. When data are abundant, this can be replaced by nonparametric models that fit reality more accurately. To some extent, this mirrors the progress that physics experienced in the middle of the previous century with the availability of computers. Rather than solving parametric approximations of how electrons behave by hand, one can now resort to numerical simulations of the associated partial differential equations. This has led to much more accurate models, albeit often at the expense of explainability.

Another difference to previous work is the acceptance of suboptimal solutions, dealing with nonconvex nonlinear optimization problems, and the willingness to try things before proving them. This newfound empiricism in dealing with statistical problems, combined with a rapid influx of talent has led to rapid progress of practical algorithms, albeit in many cases at the expense of modifying and re-inventing tools that existed for decades.

In the end, the deep learning community prides itself on sharing tools across academic and corporate boundaries, releasing many excellent libraries, statistical models, and trained networks as open source. It is in this spirit that the notebooks forming this book are freely available for distribution and use. We have worked hard to lower the barriers of access for everyone to learn about deep learning and we hope that our readers will benefit from this.

1.8. Summary¶

Machine learning studies how computer systems can leverage experience (often data) to improve performance at specific tasks. It combines ideas from statistics, data mining, and optimization. Often, it is used as a means of implementing AI solutions.

As a class of machine learning, representational learning focuses on how to automatically find the appropriate way to represent data. Deep learning is multi-level representation learning through learning many layers of transformations.

Deep learning replaces not only the shallow models at the end of traditional machine learning pipelines, but also the labor-intensive process of feature engineering.

Much of the recent progress in deep learning has been triggered by an abundance of data arising from cheap sensors and Internet-scale applications, and by significant progress in computation, mostly through GPUs.

Whole system optimization is a key component in obtaining high performance. The availability of efficient deep learning frameworks has made design and implementation of this significantly easier.

1.9. Exercises¶

Which parts of code that you are currently writing could be “learned”, i.e., improved by learning and automatically determining design choices that are made in your code? Does your code include heuristic design choices?

Which problems that you encounter have many examples for how to solve them, yet no specific way to automate them? These may be prime candidates for using deep learning.

Viewing the development of AI as a new industrial revolution, what is the relationship between algorithms and data? Is it similar to steam engines and coal? What is the fundamental difference?

Where else can you apply the end-to-end training approach, such as in Fig. 1.1.2, physics, engineering, and econometrics?